County Mayo

| County Mayo Contae Mhaigh Eo |

||

|

||

|---|---|---|

| Motto: Dia is Muire Linn (Irish) "God and Mary be with us" |

||

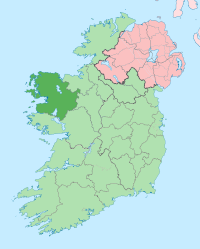

| Location | ||

|

||

| Statistics | ||

| Province: | Connacht | |

| County seat: | Castlebar | |

| Code: | MO | |

| Area: | 5,585 km2 (2,156 sq mi) (3rd) | |

| Population (2006) | 123,839 (17th) | |

| Website: www.mayococo.ie | ||

County Mayo (Irish: Contae Mhaigh Eo) is one of the twenty-six counties of the Republic of Ireland and one of the thirty-two counties of Ireland. It is located in the province of Connacht. The county was named after the village of Mayo (from Irish: Maigh Eo meaning "plain of the yew trees"), which is now generally known as Mayo Abbey. The population of the county is 123,839 according to the 2006 census.[1] The county's main towns are Castlebar and Ballina, respectively located in the centre and in the north east of the county.

Contents |

History

Prehistory

County Mayo has a long history and prehistory.[2] Throughout the county there is a wealth of archaeological remains from the Neolithic period (approx 4,000BC to 2,500BC) particularly in terms of megalithic tombs and ritual stone circles from which we can build up a picture of the lifestyle of the people who lived in Mayo during that period, some 6000 years ago.

From what we have learnt from archaeological surveys [3] we know that the first people who came to Ireland, mainly to coastal areas, as the interior was heavily afforested, arrived during the Mesolithic period (or Middle Stone Age) possibly as long as eleven thousand years ago (from approx 9,000BC).

Artefacts of Mesolithic (hunter/gatherers) people are sometimes found in 'middens', basically rubbish pits around hearths where these people would have rested for a period and cooked their food over large open fires. Midden remains regularly become exposed, as blacked areas containing charred stones, bones and shells, when cliffs are eroded. They are usually found a metre or so below the current land surface. Mesolithic people did not have major rituals associated with burial like the next people who inhabited the county in the Neolithic (New Stone Age) period.[4]

The Neolithic period took over from the Mesolithic around 6,000 years ago. People living in the Neolithic period began to farm the land, keep domesticated animals for food and milk, and stay settled in one place for longer periods. The people had skills such as making pottery, building houses from wood, weaving and knapping (stone tool working). The first farmers cleared forestry to graze livestock and grow crops. In North Mayo where the ground cover was fragile, thin soils got washed away and blanket bog crept across the landscape insiduously covering the land farmed by the Neolithic people.

Extensive pre-bog field systems have been discovered under the blanket bog landscape, particularly along the North Mayo coastline in Erris and north Tyrawley at sites such as that depicted in the Céide Fields centre on the north east coast.

The Neolithic people had developed rituals associated with burying their dead--this is why they built huge elaborate galleried stone tombs for their dead leaders, known nowadays as megalithic tombs. There are over 160 recorded megaliths in County Mayo and many more which are unrecorded. Faulagh in Erris is a particularly interesting site in relation to megalithic tombs.

Megalithic tombs

There are four distinct types of Irish megalithic tombs type--court tombs, portal tombs, passage tombs and wedge tombs--examples of all four types can be found in County Mayo.[5] Areas particularly rich in megalithic tombs include Achill, Kilcommon, Ballyhaunis, Killala and the Behy/Glenurla area around the Céide Fields.

Bronze Age (2,500 BC to approx 500 BC)

Megalithic tomb building continued into the Bronze Age when metal began to be worked for tools alongside the stone tools. The Bronze Age lasted from approx 4,500 years ago to 2,500 years ago (i.e. 2,500BC to 500BC)--archaeological remains from this period include stone alignments, stone circles and fulachta fiadh (early cooking sites). They continued to bury their chieftains in megalithic tombs which changed design during this period, more being of the wedge tomb type and cist burials.

Iron Age (500 BC to 500 AD approx)

Around 2,500 years ago the Iron Age took over from the Bronze Age as more and more metalworking took place. At the same period the Roman Empire was at its height in Britain but it is not thought that the Roman Empire extended into Ireland to any large degree. Remains from this period, which lasted until the Early Christian period began about 325AD (with the arrival of St. Patrick into Ireland, as a slave) include crannógs (Lake dwellings, promontory forts, ringforts and souterrains of which there are numerous examples across the county. The Iron Age was a time of tribal warfare with kingships, each fighting neighbouring kings, vying for control of territories and taking slaves. Territories were marked by tall stone markers, Ogham stones, using the first written down words using the Ogham alphabet. The Iron Age is the time period in which the tales of the Ulster Cycle and sagas took place. The Táin Bó Flidhais which took place mainly in Erris sets the scene well.

Early Christian Period (325 AD - 800 AD approx)

Christianity came to Ireland around the start of the 5th century AD. It brought many changes including the introduction of writing and recording events. The tribal 'tuatha' and the new religious settlements existed side by side. Sometimes it suited the chieftains to become part of the early Churches, other times they remained as separate entities. St. Patrick (4th century AD) may have spent time in County Mayo and it is believed that he spent forty days and forty nights on Croagh Patrick praying for the people of Ireland.[6] From the middle of the sixth century hundreds of small monastic settlements were established around the county.

Some examples of well-known early monastic sites in Mayo include Mayo Abbey, Aughagower, Ballintubber, Errew, Cong, Killala, Turlough on the outskirts of Castlebar, and island settlements off the Mullet Peninsula like the Inishkea Islands, Inishglora and Duvillaun.

In 795AD the first of the Viking raids took place. The Vikings came from Scandinavia to raid the monasteries as they were places of wealth with precious metal working taking place in them. Some of the larger ecclesiastical settlements erected round towers to prevent their precious items being plundered and also to show their status and strength against these pagan raiders from the north. There are round towers at Aughagower, Balla, Killala, Turlough and Meelick. The Vikings established settlements which later developed into towns (Dublin, Cork, Wexford, Waterford etc..) but none were in County Mayo.

Anglo-Normans (12th to 16th centuries)

From 1169 AD when one of the warring 'kings' (Dermot MacMurrough) in the east of Ireland appealed to the King of England for help in his fight with a neighbouring king, the response of which was the arrival of the Anglo-Norman colonisation of Ireland. County Mayo came under Norman control in 1235AD. The Norman conquest meant the eclipse of many Gaelic lords and chieftains, chiefly the O'Connors of Connacht. It is a well-known fact however, that within a few generations these new colonisers became "more Irish than the Irish themselves" adopting language, religion, dress, customs and marrying into Irish families. Surnames with Norman origins are common in County Mayo today. They include Barrett, Bourke, Burke, Costello, Culkin, Davitt, Fitzmaurice, Gibbons, Jennings, Joyce, McEvilly, Nally, Padden, Staunton and Walsh.[7]

The Anglo Normans encouraged and established many religious orders from the European continent to settle in Ireland. Mendicant orders--Augustinians, Carmelites, Dominicans and Franciscans began new settlements across Ireland and built large churches, many under the patronage of prominent Gaelic families. Some of these sites include Cong, Strade, Ballintubber, Errew, Burrishoole Abbey and Mayo Abbey.[8] The Irish and the English were close companions as both were Catholic countries. Many Irish people such as Grace O'Malley, the famous pirate queen had close friendships with the English monarchy and the English kings and queens were welcome visitors to Irish shores, despite the early plantations of settlers started during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I.

In the summer of 1588 the galleons of the Spanish Armada were wrecked by storms along the west coast of Ireland. Some of the hapless Spaniards came ashore in Mayo, only to be robbed and imprisoned, and in many cases slaughtered.

Almost all the religious foundations set up by the Anglo Normans were suppressed in the wake of the Reformation in the 16th century.[9]

17th and 18th centuries

Pirate Queen Grace O'Malley is probably the best known person from County Mayo around the turn of the 17th century. The Irish at the time of the reign of Queen Elizabeth I had close relationships with the British monarchy who were regarded at that time as the King or queen of Ireland also. In the 1640s when Oliver Cromwell overthrew the English monarchy and set up a parliamentarian government, Ireland suffered severely. With a stern regime in absolute control needing to pay its armies and friends, the need to pay them with grants of land in Ireland led to the 'to hell or to Connaught' policies.[10] Displaced native Irish families from other (eastern and southern mostly) parts of the country were either forced to leave the country, often as slaves, or (if they had been well behaved and compliant with the orders of the parliamentarians) awarded grants of land 'west of the Shannon' and put off their own lands in the east. The land in the west was divided and sub-divided between more and more people as huge estates were granted on the best land in the east to those who best pleased the English.[11]

For the vast majority of people in County Mayo the eighteenth century was a period of unrelieved misery. Because of 'the penal laws', Catholics had no hope of social advancement while they remained in their native land. Some, like William Brown (admiral) (1777–1857), left Foxford with his family at the age of nine and thirty years later was an admiral in the fledgling Argentine Navy. Today he is a national hero in that country.[12]

Unrest in Ireland was felt just as keenly across Mayo. By 1798 the Irish were ready for rebellion despite or maybe because of, their suppression by the government. The French came to help the Irish cause. General Humbert, from France landed in Killala with over 1,000 officers where they started to march across the county towards Castlebar where there was an English garrison. Taking them by surprise Humbert's army was victorious. He established a 'Republic of Connacht' with one of the Moore family from Moore Hall near Partry. Humbert's army marched on towards Sligo, Leitrim and Longford where they were suddenly faced with a massive English army and were forced to surrender in less than half an hour. The French soldiers were treated honourably, but for the Irish the surrender meant slaughter. Many died on the scaffold in towns like Castlebar and Claremorris, where the high sheriff for County Mayo, the Honourable Denis Browne, M.P., brother of Lord Altamont, wreaked a terrible vengeance - thus earning for himself the nickname which has survived in folk-memory to the present day, 'Donnchadh an Rópa' (Denis of the Rope).

In the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries sectarian tensions arose as evangelical Protestant missionaries sought to 'redeem the Irish poor from the errors of Popery. One of the best known was the Rev. Edward Nangle's mission at Dugort in Achill[13]. These too were the years of the campaign for Catholic Emancipation and, later, for the abolition of the tithes, which a predominately Catholic population was forced to pay for the upkeep of the clergy of the Established (Protestant) Church.

19th and 20th centuries

During the early years of the nineteenth century, famine was a common occurrence, particularly where population pressure was a problem. The population of Ireland grew to over eight million people prior to the Irish Famine of 1845/47 The Irish people depended on the potato crop for their sustenance. Disaster struck in August 1845, when a killer fungus (later diagnosed as Phytophthora infestans) started to destroy the potato crop. When widespread famine struck, about a million people died and a further million left the country. People died in the fields from starvation and disease. The catastrophe was particularly bad in County Mayo, where nearly ninety per cent of the population depended on the potato as their staple food. By 1848, Mayo was a county of total misery and despair, with any attempts at alleviating measures in complete disarray.[14]

There are numerous reminders of the Great Famine to be seen on the Mayo landscape: workhouse sites, famine graves, sites of soup-kitchens, deserted homes and villages and even traces of undug 'lazy-beds' in fields on the sides of hills. Many roads and lanes were built as famine relief measures. There were nine workhouses in the county: Ballina, Ballinrobe, Belmullet, Castlebar, Claremorris, Killala, Newport, Swinford and Westport.[15]

A small poverty-stricken place called Knock, County Mayo, made headlines when it was announced that an apparition of the Blessed Virgin Mary, St. Joseph and St. John had taken place there on 21 August 1879, witnessed by fifteen local people.[16]

.jpg)

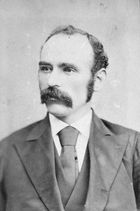

A national movement was initiated in County Mayo during 1879 by Michael Davitt, James Daly, and others, which brought about the greatest social change ever witnessed in Ireland. Michael Davitt, a labourer whose family had moved to England joined forces with Charles Stewart Parnell to win back the land for the people from the landlords and stop evictions for non payment of rents.[17]

A new word came into the English language through an incident that occurred in Mayo. An English landlord called Captain Charles Cunningham Boycott could get no workers to do anything for him, so unpleasant as he was to them, so he brought in Protestant workers from elsewhere. He spent so much on security and protection for them that his harvest cost him a fortune and also nobody in the area would serve him in shops, or deal with him. This ostracisation became known as 'boycotting' and Captain Boycott was left with no option but to leave Mayo and take his family with him to England.[18]

The 'Land Question' was gradually resolved by a scheme of state-aided land purchase schemes.[19] The tenants became the owners of their lands under the newly set-up Land Commission.

A Mayo nun, Mother Agnes Morrogh-Bernard (1842–1932), set up the Foxford Woollen Mill in 1892. She made Foxford synonymous throughout the world with high quality tweeds, rugs and blankets.[20][21]

Mayo has remained an essentially rural community to the present day.

Clans and families

In the early historic period, what is now County Mayo consisted of a number of large kingdoms, minor lordships and tribes of obscure origins. They included:

- Calraige - pre-historic tribe found in the parishes of Attymass, Kilgarvan, Crossmolina and the River Moy

- Ciarraige - settlers from Munster found in south-east Mayo around Kiltimagh and west County Roscommon

- Conmaicne - a people located in the barony of Kilmaine, alleged descendants of Fergus mac Róich

- Fir Domnann - branch of the Laigin, originally from Britain, located in Erris

- Gamanraige - pre-historic kings of Connacht, famous for battle with Medb & Ailill of Cruachan in Táin Bó Flidhais. Based in Erris, Carrowmore Lake, Killala Bay, Lough Conn.

- Gailenga - kingdom extending east from Castlebar to adjoining parts of Mayo

- Uí Fiachrach Muidhe - a sept of the Connachta, based around Ballina, some of whom were kings of Connacht

- Partraige - apparently a pre-Gaelic people of Lough Mask and Lough Carra, namesakes of Partry

- Ui Mail - kingdom surrounding Clew Bay, east towards Castlebar, its rulers adopted the surname O'Malley

Between the reigns of Kings of Connacht Cathal mac Conchobar mac Taidg (973-1010) and Tairrdelbach Ua Conchobair (1106-1156), all these territories were incorporated into the kingdom of Connacht and ruled by the Siol Muirdaig dynasty, based first around Rathcroghan in County Roscommon, and from c. 1050 at Tuam in County Galway. The families of O'Malley and O'Dowd of Mayo served as Admiral's of the fleet of Connacht, while families such as O'Lachtnan, Mac Fhirbhisigh, O'Cleary were ecclesiastical and bardic clans.

During the 1230s, the Anglo-Normans and Welsh under Richard Mór de Burgh (c. 1194-1242 invaded and settled in the county, introduceing new families such as Burke, Gibbons, Staunton, Prendergast, Morris, Joyce, Walsh, Barrett, Lynott, Costello. Following the collapse of the lordship in the 1330s, all these families became estranged from the Anglo-Irish administration based in Dublin and assimilated with the Gaelic-Irish, adopting their language, laws and culture.

The most powerful clan to emerge during this era were the Mac William Burkes, also known as the Mac William Iochtar (see Burke Civil War 1333-1338, descended from Sir William Liath de Burgh, who defeated the Gaelic-Irish at the Second Battle of Athenry in August 1316. They were frequently at war with their cousions, Clanricarde of Galway, and in alliance with or against various factions of the O'Conor's of Siol Muiredaig and O'Kelly's of Uí Maine. The O'Donnell's of Tyrconnell regularly invaded in an attempt to secure their right to rule.

From c. 1541 the lords of Mayo were in regular conflict with the English crown, and were only fully subborned to them after 1603. By then the term County Mayo had come into use. Protestant settlers from Scotland, England, and elsewhere in Ireland, settled there in following decades. Many would be killed or forced to flee because of the 1641 Rebellion, during which a number of massacres were committed by the Catholic Gaelic Irish, most notably at Shrule in 1642. Fully a third of the overall population perished due to warfare, famine and plague between 1641 and 1653, with several areas remaining disturbed and frequented by Raparees into the 1670s. Mayo does not seem to have suffered much in during the Williamite War in Ireland, though many natives were outlawed and exiled. The county would remain fairly peaceful till the events of 1798.

Surnames

The principal surnames of Mayo, according to figures taken from the register of civil births index of 1890, were: 1 - Walsh 2 - Gallagher 3 - Kelly 4 - Malley/O'Malley 5 - Moran 6 - Duffy 7 - McHale 8 - Gibbons 9 - Joyce 10 - Connor/O'Connor 11 - Conway 12 - Higgins 13 - Murphy 14 - Burke/Bourke 15 - Reilly/O'Reilly 16 - Durkan 17 - Doherty 18 - McHugh 19 - Sweeney 20 - Lyons

Of these, Walsh (Breathnach), Gibbons, Joyce, Burke/Bourke are of Anglo-Norman origin. Gallagher and Sweeney/Mac Sweeney were Galloglass clans. Kelly, Duffy, Connor/O'connor, Durkan, Doherty, Conway, Lyons, Higgins, McHugh, are native to other parts of Ireland. Malley/O'Malley, Moran, McHale, Murphy, are all native to Mayo.[22]

Other surnames found in Mayo include: Ainsworth, Barrett, Basquille, Bourke, Bowman, Breathnach (Walsh), Cafferky, Carney/Kearney, Cawley, Chambers, Coleman, Costello, Coyle, Dean, Devilly, Derrig, Devir, Diamond, Donnelly, Flynn, Garvin, Gildea, Gilmartin, Grealish, Healy, Heneghan, Horan, Jennings, Jordan, Lavelle, Lawless, Loftus, Lydon, Lynott, Macken, Maughan, Morley/O'Muraile, Mortimer, Moyles, Moylette, McDonnell, McEvilly, McGing, McLoughlin, McManamon, McManus, McNally/Nally, McPhilbin, McTige, Nolan, Ormsby, O'Boyle, O'Cleary, O'Donnell, O'Dowd, Padden, Rutlidge, Sammon, Staunton, Sullivan, Thornton, Tierney, Waldron.

Geography

Mayo is the third largest of Ireland’s 32 counties in area and 15th largest in terms of population[23]. It is the second largest of Connacht’s five counties in both size and population. There is a distinct geological difference between the north and the south of the county. The north consists largely of poor subsoils, and is covered with large areas of extensive Atlantic blanket-bog, whereas the south is largely a limestone landscape in common with almost 70% of the 'green' fields of Ireland. Agricultural land in the south is, therefore, more productive than that in the north.

- The highest point in Mayo and Connacht is Mweelrea, at 814 m (2,671 ft).

- The river Moy in the northeast of the county is renowned for its salmon fishing.

- Ireland's largest island, Achill Island, lies off Mayo's west coast.

- Mayo has Ireland's highest cliffs (third highest in Europe) at Croaghaun, Achill island while the Benwee Head cliffs in Kilcommon Erris drop almost perpendicularly 900 feet into the Atlantic Ocean. There is a spectacular viewing point on the top of the cliffs opposite the entrance to the Céide Fields near Ballycastle in North Mayo.

- The north-west areas of County Mayo have some of the best renewable energy resources in Europe, if not the world, in terms of wind resources, ocean wave, tidal and hydroelectric resources.

Sub-divisions

County Mayo is divided into nine baronies, four in the northern area and five in the south of the county:

North Mayo

- Erris (north west containing Belmullet, Gweesalia, Bangor Erris, Kilcommon etc..)

- Burrishoole (west Mayo containing Achill, Mulranny and Newport, County Mayo)

- Gallen (east Mayo containing Bonniconlon, Foxford)

- Tyrawley (north east containing Ballina, Ballycastle, Killala)

South Mayo

- Clanmorris, (south east - Claremorris and Balla)

- Costello (east south east containing Kilkelly Ballyhaunis) etc..

- Murrisk south west containing Westport, Louisburgh, Croagh Patrick etc..)

- Kilmaine (south containing Ballinrobe, Cong etc...)

- Carra (south containing Castlebar, Partry etc..)

Towns and villages

Castlebar and Ballina are the two most populous towns in the county, with 17,891 and 10,146 residents respectively according to the 2006 census; Ballina being much larger by land area. These are followed by Westport, a popular tourist town, which has some 5,000 residents. The fourth largest town is Claremorris, a market town, with a population of 3,170 in the 2006 census returns.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Demographics

| Historical populations | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | %± |

| 1659 | 29,967 | — |

| 1821 | 293,112 | 878.1% |

| 1831 | 366,328 | 25.0% |

| 1841 | 388,887 | 6.2% |

| 1851 | 274,499 | −29.4% |

| 1861 | 254,796 | −7.2% |

| 1871 | 246,030 | −3.4% |

| 1881 | 245,212 | −0.3% |

| 1891 | 219,034 | −10.7% |

| 1901 | 199,166 | −9.1% |

| 1911 | 192,177 | −3.5% |

| 1926 | 172,690 | −10.1% |

| 1936 | 161,349 | −6.6% |

| 1946 | 148,120 | −8.2% |

| 1951 | 141,867 | −4.2% |

| 1956 | 133,052 | −6.2% |

| 1961 | 123,330 | −7.3% |

| 1966 | 115,547 | −6.3% |

| 1971 | 109,525 | −5.2% |

| 1979 | 114,019 | 4.1% |

| 1981 | 114,766 | 0.7% |

| 1986 | 115,184 | 0.4% |

| 1991 | 110,713 | −3.9% |

| 1996 | 111,524 | 0.7% |

| 2002 | 117,446 | 5.3% |

| 2006 | 123,839 | 5.4% |

| [24][25][26][27][28][29] | ||

The county has experienced perhaps the highest emigration out of Ireland. In the 1840s-1880s, waves of emigrants left the rural townlands of the county. Initially triggered by the Great Famine and then in search of work in the newly industrialising England, Scotland and the United States, the population fell considerably. From 388,887 in 1841, the population fell to 199,166 in 1901. The population reached a low of 109,525 in 1971 as emigration continued.

Flora and fauna

A survey of the terrestrial and freshwater algae of Clare Island was made between 1990 and 2005 and published in 2007. Records of the algae in Volume 6.[30]

Consultants working for the Corrib gas project have carried out extensive surveys of wildlife flora and fauna in Kilcommon Parish, Erris between 2002 and 2009. This information is published in the Corrib Gas Proposal Environmental impact statements 2009 and 2010[31]

Places of interest

|

|

Media

- Local newspapers include the Mayo News, the Connaught Telegraph, the Connacht Tribune, Western People, and Mayo Advertiser, which is Mayo's only free newspaper[32].

- Local radio stations include Community Radio Castlebar and M.W.R. (Mid West Radio).

The locally made feature documentary 'Pipe Down' won best feature documentary at Waterford film festival 2009 http://www.vimeo.com/8668733

Podcasts

24 radio programmes highlighting the people and history of Mayo towns and heritage sites narated by local guest presenters were produced in 2007 and 2008 called A Heritage Tour and these form the basis for a web based series of free audio podcasts under the title Mayo's Heritage.[33]

This website also contains podcasts featuring The Mayo Peace Park [9] The annual bell ringing at Lahardane to commemorate the 14 people from The Parish of Addergoole who were on board The RMS Titanic, 11 of whom perished [10] And The Story of Bob of The Reek about a hermit who lived on Croagh Patrick at the beginning of The 19th century [11] as well as interviews with and performances by many Mayo writers [12]

Energy

Energy controversy

There is local resistance to Shell's decision to refine raw gas from the Corrib gas field at an onshore refinery. In 2005, five local men were jailed for contempt of court after refusing to facilitate Shell's work. Subsequent protests against the project led to the Shell to Sea and related campaigns.

Energy Audit

The Mayo Energy Audit 2009-2020 is an investigation into the implications of peak oil and subsequent fossil fuel depletion for a rural county in west of Ireland. The study draws together many different strands to examine current energy supply and demand within the area of study, and assesses these demands in the face of the challenges posed by the declining production of fossil fuels and expected disruptions to supply chains, and by long term economic recession.[34][35][36]

Sport

Mayo is noted for its Gaelic football team, and their efforts to capture the All-Ireland Football Title in recent years. They last won the Sam Maguire Cup in 1951, when the team was captained by Seán Flanagan. Mayo's most recent All-Ireland final appearances have been in 1989, 1996, 1997, 2004 and 2006. They defeated a hotly tipped Dublin team in the 2006 All Ireland Semi Final in what is generally acknowledged to be one of the best games ever played in Croke Park, Mayo winning by one point.

People

- Richard Bourke, 6th Earl of Mayo - Viceroy of India 1869-72.

- Browne family

- Admiral William Brown (1777 to 1857) - born in Foxford, founder of the Argentine Navy.

- Patrick Browne (1720–1790) - doctor and botanist of Jamaica.

- Brian Rua U'Cearbhain - 17th century prophet from Erris.

- Willie Corduff - Winner of Goldman Environmental Prize 2007.

- Jerry Cowley - GP of note.

- Michael Davitt - founder of the Land League, born in Mayo. The bridge to Achill is named after him as well as Castlebar's local secondary school (Davitt College).

- Richard Douthwaite - economist and campaigner from Westport

- Frank Durkan - New York City human rights attorney best-known for having represented numerous members of the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA), including avowed gun-runner and pivotal North American member of the IRA George Harrison, who stood trial, and was acquitted, in 1982 and Desmond Mackin - accused of shooting a British soldier.

- Earl of Mayo (Bourke)

- Michael Feeney, MBE - Chairman and Founder of Mayo Peace Park.[37]

- Seán Flanagan (1922– 1993) - senior Fianna Fáil politician and Gaelic footballer. He served under Taoiseach Jack Lynch as Minister for Health (1966–1969) and Minister for Lands (1969–1973).

- Adrian Flannelly - Irish Radio Network host from 1970.

- Flidais - the heroine of the Ulster Cycle Erris legend of the Táin Bó Flidhais.

- James Owen Hannay aka George A. Birmingham - author of such novels about County Mayo as The Seething Pot (1905) and Hyacinth (1906).

- John Healy - author and journalist (1930–1991).

- Enda Kenny - politician, leader of Fine Gael since 2002.

- Marquess of Sligo (Browne)

- Ciarán McDonald - Gaelic football player.

- John McDonnell (born July 2, 1938) - athletics coach. He has won more national championships (42) than any coach in any sport in the history of American collegiate athletics.

- Paul O'Dwyer - President of New York City Council, prominent New York City human rights attorney, supporter of Irish nationalism, and defender of several Irish Republican Army gunmen from deportation, including "The Fort Worth Five" and Vincent Conlon.

- William O'Dwyer - mayor of New York City from 1946–1950.

- Bernard O'Hara (b. 1945) - Irish historian.

- Grace O'Malley - 16th century pirate queen and chieftain of the clan O’Malley, also known as Granuaile.

- Michael Ring - Most popular Fine Gael politician in Mayo.

- Mary Robinson (born in Ballina, 1944) — first female President of Ireland (1990–1997), and United Nations High Commissioner for Human rights.

- Aoibhinn Ní Shúilleabháin (born in Carnacon in 1983) - winner of the 2005 Rose of Tralee contest. She is the 47th Rose and the first from County Mayo.

- Frank Stagg - IRA Hunger striker.

- Louis Walsh (born 5 August 1952) - pop music manager.

See also

- Táin Bó Flidhais

- Castlebar transmitter

- Connacht Irish

- List of abbeys and priories in the Republic of Ireland (County Mayo)

- Achill

- Westport

- Louis Walsh

- Mayo College

- Mayo County Council

- Westport House

- Mayo Peace Park

References

- ↑ Census 2006 - Population of each province, county and city

- ↑ http://www.mayococo.ie/en/Services/Archaeology/

- ↑ http://www.mayococo.ie/en/Services/Archaeology/Glossary/

- ↑ http://www.wesleyjohnston.com/users/ireland/past/pre_norman_history/neolithic_age.html

- ↑ http://www.environ.ie/en/Publications/Heritage/NationalMonuments/FileDownLoad,2293,en.pdf

- ↑ http://www.mayo-ireland.ie/Mayo/History/FullHist.htm

- ↑ http://www.mayo-ireland.ie/Mayo/History/FullHist.htm

- ↑ http://www.uni-due.de/LI/Anglo_Norman.htm

- ↑ http://www.wesleyjohnston.com/users/ireland/past/history/15411598.html

- ↑ http://www.libraryireland.com/IrishIndependence/22.php

- ↑ http://www.irish-society.org/Hedgemaster%20Archives/Cromwell_2.htm

- ↑ http://www.con-telegraph.ie/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=326:illustrious-and-amazing-career-of-admiral-william-brown&catid=52:mayo-history&Itemid=89

- ↑ http://www.mayococo.ie/en/Services/Environment/LeisureAmenities/Beaches/Doogort/

- ↑ http://www.libraryireland.com/articles/FamineBelmulletFriends/index.php

- ↑ http://www.mayohistory.com/H18to19.htm

- ↑ http://www.knock-shrine.ie/witnesses-accounts

- ↑ http://www.irishidentity.com/stories/parnelldav.htm

- ↑ http://www.askaboutireland.ie/learning-zone/primary-students/looking-at-places/mayo/michael-davitt/captain-boycott/

- ↑ http://www.encyclopedia.com/doc/1E1-IrishLan.html

- ↑ http://www.discoverireland.com/us/ireland-things-to-see-and-do/listings/product/?fid=FI_444

- ↑ http://www.museumsofmayo.com/foxford1.htm

- ↑ The Principal Surnames of Mayo, Nollaig O Muraile, in Mayo: Aspects of its Heritage, p. 83, edited by Bernard O'Hara, 1982)

- ↑ Corry, Eoghan (2005). The GAA Book of Lists. Hodder Headline Ireland. pp. 186–191.

- ↑ For 1653 and 1659 figures from Civil Survey Census of those years, Paper of Mr Hardinge to Royal Irish Academy March 14, 1865.

- ↑ Census for post 1821 figures.

- ↑ http://www.histpop.org

- ↑ http://www.nisranew.nisra.gov.uk/census

- ↑ Lee, JJ (1981). "On the accuracy of the Pre-famine Irish censuses". In Goldstrom, J. M.; Clarkson, L. A.. Irish Population, Economy, and Society: Essays in Honour of the Late K. H. Connell. Oxford, England: Clarendon Press.

- ↑ Mokyr, Joel; O Grada, Cormac (November). "New Developments in Irish Population History, 1700-1850". The Economic History Review 37 (4): 473–488. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0289.1984.tb00344.x. http://www3.interscience.wiley.com/journal/120035880/abstract.

- ↑ Guiry, M. D., John, D. M., Rindi, F. and McCarthy, T. K., eds. (2007) New Survey of Clare Island. Volume 6: The Freshwater and Terrestrial Algae. Dublin: Royal Irish Academy. ISBN 13: 978-1-904890-31-7

- ↑ http://www.corribgaspipelineabpapplication.ie/. From the latest E.I.S. submitted in June 2010 click 'Further Information'. then select 'Volume 2 of 3 Appendices Books 1-6' then select 'Volume 2 Book 3 of 6' where will be found eleven extensive tomes dealing with the wildlife, marine, freshwater and terrestrial flora and fauna of a small area of Kilcommon parish.

- ↑ http://www.advertiser.ie/index.php/mayo

- ↑ http://www.podcasts.ie/2010/05/mayos-heritage/

- ↑ http://www.sustainability.ie/energyplan.html

- ↑ http://www.energybulletin.net/node/47704

- ↑ http://zone5.org/2009/01/mayo-energy-audit/

- ↑ http://mayomemorialpeacepark.org Mayo Peace Park and Garden of Remembrance

External links

- Corrib Gas Pipeline ABP Application

- Mayo.ie

- Mayo County Council's website

- Mayo News

- County Mayo: An Outline History by Bernard O'Hara and Nollaig Ó'Muraíle

- Connaught Telegraph

- Western People

- MidWest Radio

- MayoToday.ie - Online News for County Mayo

- Podcasts.i.e. Mayos Heritage

- PureMayo - Pocket guide to mayo highlights

- Mayo Peace Park and Garden of Remembrance

- aboutmayo.com - News Aggregator for County Mayo

- Trailer for 'The Pipe' released 8 July 2010 - Galway Film Festival

- Pipe Down, prize winning documentary from Ireland (Vimeo, Flash 10)

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||